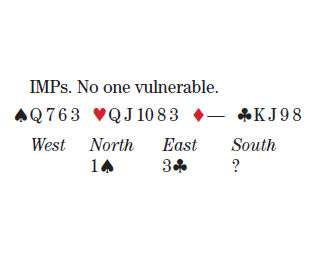

What’s your call?

| 3♦ | 3♥ | 3♠ | 3NT | |

| 4♣ | 4♦ | 4♥ | 4♠ | 4NT |

| 5♣ | 5♦ | 5♥ | 5♠ | 5NT |

| 6♣ | 6♦ | 6♥ | 6♠ | 6NT |

| 7♣ | 7♦ | 7♥ | 7♠ | 7NT |

| Dbl | Pass |

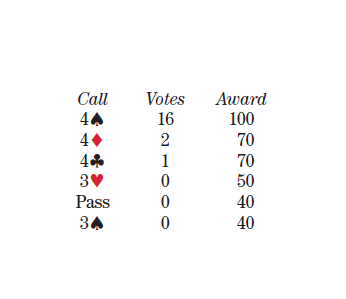

What’s it worth to you?

Most of the panelists deem their hand too good to bid 3-only-♠, but, with the suspect club values, not good enough for a cuebid. So they settle on 4♠.

Walker calls the hand “way too short in helpful high cards for the stronger raises (4♣ and 4♦).” Cohen recites, “Support with support,” and adds, “Jumping to 4♠ here is not weak.”

Falk says, “I hate to cuebid when I have no prime cards outside clubs (and not the ♣A). Partner either has a singleton or void in clubs, or he can get a club ruff, so my clubs are useless and this hand is not as wonderful as it appears. I assume 4♦ would be a splinter, but with no control in either hearts or spades, that’s too much also.”

“Lots of offense,” say the Coopers, who bid 4♠, “and we don’t want to make it easy for the opponents to find their diamond fit.”

Weinstein describes the jump to 4♠ as “a good limit raise up to a bad game force. Cuebidding would show more and this hand does not evaluate to more. The club holding isn’t as good as it seems, and we lack controls.”

The Sutherlins bid 4♠ — “enough for game, not enough to make a move toward slam. A 4♦ splinter is flawed in that we are void and have none of the five key cards. Also, it might let the opponents find a good diamond save.”

Neither of those reasons stop Robinson or Kennedy from exploring whether diamond shortness interests partner. Says Robinson, “I don’t know what my void in diamonds is worth, but my hand could be valuable opposite hearts and spades. This gives partner a chance to bid 4♥ (last train), which gives me a chance to get out, since I have no other first-round controls.”

Sanborn wants to establish ownership of the deal should the auction continue to continue, so she cuebids 4♣. “Not a slam try,” she assures. “Now, in any competitive situation, passes become forcing and meaningful.”